Stanisław Cywiński – norwidolog i filozof

2023-09-10

Eliza Orzeszkowa o Polesiu

2023-09-15David F. Swenson: Kierkegaard

The outer aspects of Kierkegaard's career suggest the placid and uneventful life of a student and man of letters. Born in Copenhagen on the 5th of May, 1813, the youngest son of a merchant of means, he received the humanistic discipline of a classical school, and was enrolled in the University at the age of eighteen. The ten years following were spent in somewhat discursive studies, ranging over the fields of esthetics, philosophy, and theology. At twenty-seven he received the degree of Magister artium, and soon thereafter entered into an engagement of marriage, broken after a year upon his own initiative. He remained unmarried, and from this time until his death, which took place on the 11th of November, 1855, he devoted himself unremittingly to his literary labors, unfolding an extraordinary productivity.

Kierkegaard was endowed with a sensitive organism, and under the calm surface of his outward life there stirred a tense spiritual vitality. The trait which Wordsworth eulogizes as a mark of spiritual elevation, "the capacity to be excited to significant feeling without the application of gross or violent stimulants," was his in an extraordinary degree. Events which in the lives of most men would have passed without creating a ripple upon the surface, stirred his soul to its depths; and hence the apparent exaggeration which so many of his critics have found in his interpretation of himself and his experiences. The man of genius is naturally characterized by freshness and fulness of feeling, and Kierkegaard's personal experiences were certainly deeply felt; so profoundly, indeed, that they served to stimulate in him a reflection of universal significance.

Both parents were of peasant stock. The father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard, came to Copenhagen as a boy of twelve, and was apprenticed to an uncle engaged in trade. He eventually set up for himself, achieved success and retired at forty with a competence regarded as considerable for the times. This retirement from business synchronized with his second marriage, a year after the death of his first wife. Of the seven children of this second marriage, Soren Aabye was the youngest. Thus the father was already fifty-seven years old at the time of Soren's birth, while his mother was forty-five.

Soren's mother had been her husband's housekeeper. Of a cheerful and domestic disposition, she seems to have been but little capable of entering into the intellectual life of her two gifted sons, and appears to have exerted a minimum of influence upon Kierkegaard's development. His journals maintain silence with regard to her.

The father was a dominant figure, austere and precise. A deep strain of melancholy in his disposition, nurtured by unhappy and disquieting memories, tended in its turn to keep these memories alive. From this melancholy he sought relief in a pietistic religiosity, and to some extent, it appears, in philosophical reading. To him Kierkegaard attributes the deepest formative influences of his life. A merchant who retires at forty from a successful business career in order to have leisure to repent his sins, read Wolffian metaphysics, and bring up his children in the fear of God, cannot be set down as an ordinary or commonplace character; and it is not surprising that his influence upon the son should have been profound.

The melancholy which was the common heritage of father and son can be described by citing a single characteristic trait. One day while herding sheep on the bare Jutland heath, embittered by his privations and oppressed by loneliness, the elder Kierkegaard, who was then a boy of eleven or twelve, had mounted a hill and assailed with curses the God who had condemned him to so wretched an existence. In Kierkegaard"s journal for the year 1846 there is a reference to this incident in the following terms: "The terrible fate of the man who had once in childhood mounted a hill and cursed God, because he was hungry and cold, and had to endure privations while herding his sheep— and who was unable to forget it even at the age of eighty-two." When after Kierkegaard's death this passage was shown to his surviving elder brother, Bishop Peder Christian Kierkegaard, he burst into tears and said: "That is just the story of our father, and of his sons as well." Elsewhere, in Stages on the Way of Life, Kierkegaard suggests that these dark moods served to link the father and the son in a fellowship of secret and unexpressed sympathy.

"There once lived a father and a son. A son is a mirror in which the father sees himself reflected, and the father is a mirror in which the son sees himself as he will be in the future. But these two did not often look at one another in this manner, for their daily intercourse was carried on through the medium of a gay and lively conversation. But sometimes it happened that the father would pause and turn with sad face toward the son, saying as he gazed into his eyes: 'Poor boy, you are the victim of a silent despair.' This was all that ever passed between them; no explanation of the meaning of these words was ever vouchsafed, nor any discussion of how far they might possibly be true. The father thought that he was responsible for the boy's melancholy, and the son thought that it was he who caused his father so much grief — but not a word was ever exchanged between them on the subject."

There are two other phases of Kierkegaard's boyhood, and of his father's influence upon the development of his mind, which I shall allow him to describe in his own words, quoting the sketch given of Johannes Climacus, the principal character in De omnibus dubitandum est, an unfinished metaphysical essay, written by Kierkegaard in 1842-3, and undoubtedly autobiographical in character.

"His home-life offered but few diversions. He was scarcely ever permitted to go out, and thus he became accustomed, at an early age, to attend to himself and to his own thoughts. His father was very strict, and dry and prosaic on the surface; but underneath this coarse and unpretentious exterior he preserved a glowing fancy, which not even his extreme old age was able to dull. When Johannes sometimes asked for permission to go out, he was most often refused; but occasionally, as if to make up for this refusal, the father proposed a walk together up and down the room. This seemed at first a poor substitute; and yet, like his father's coarse gray coat, it concealed under its plain exterior something very different from that which appeared on the surface. The proposal accepted, it was for Johannes himself to decide where to go. They passed out the gate and visited a neighboring palace; or went to the seashore, or wandered about the streets, all at the boy's pleasure. For the father's imagination was powerful enough to create a realizing sense of anything and everything the boy desired. While they walked up and down, the father described the sights along the way; they greeted the passers-by; the vehicles rumbled and drowned the father's voice; the dainties displayed by the fruit- woman on the corner seemed more alluring than ever. When they were on ground familiar to Johannes, everything was given a description so vivid and minute that not the smallest detail was overlooked. When the way took them to scenes new and unfamiliar, the father knew how to draw so explicit a picture, and give it so vivid an intuition, that after but half an hour of this promenade Johannes was as tired and overwhelmed by his impressions as if he had been out of doors an entire day.

He soon learned how to practice his father's magic art for himself. A dramatic representation supplanted the former epic narrative; for they conversed together on the way. When they walked amidst scenes with which Johannes was familiar, they prompted one another faithfully, lest anything should be overlooked; when the way was strange, Johannes trusted his fancy to combine the elements of his memory into pictures, while his father's all-powerful imagination brought into being every least detail, utilizing every childish wish as an ingredient in the drama. To Johannes it seemed as if he were witnessing, during the course of their conversation, a world coming into being; it was as if his father were the Creator, and he himself a favorite, permitted freely to introduce his own childish fancies into the creative process. For he was never repressed, and his father was never at a loss; every suggestion tendered was made use of, and always to Johannes' complete satisfaction.

"With an all-powerful imagination the father combined an invincible dialectic. And hence when at times the father was engaged in argument with a neighbor, Johannes was all ears; and this so much the more, as everything in these discussions was arranged with ceremonious order and precision. His father never interrupted the opponent, but let him speak through to the end; when he appeared to have finished, he always cautiously asked him if there was anything more he wished to say, before beginning his answer. Johannes had followed the argument with concentrated attention, and was, in his own way, a truly interested participant. There came a pause, and then the father's reply; all was changed in the twinkling of an eye. How it was changed was a mystery to the boy, but his mind was fascinated by the spectacle. The opponent spoke in rebuttal, and Johannes was still more deeply attentive, if possible, than before; he wanted to bear every point in mind. The opponent approached his peroration, and Johannes could almost hear his own heart beat, so impatient was he to hear the outcome of the argument. Then came the father's reply, and in a moment everything was changed. The things that had seemed clear before, suddenly became inexplicable; the things that had seemed certain became doubtful, and their very opposites were made to appear evident.

"What other children possessed in the enchantments of poetry and the surprises of adventure, Johannes had in the calm of a vivid intuition and the swiftly changing perspectives of dialectics. When he became older he had no need to cast his playthings aside, for he had learned to play with that which was to be the serious business of his life; and yet it never lost its allurement. A girl plays with her dolls until at last the doll is transformed into a lover, for a woman's entire life is love. A similar continuity characterized Johannes' life, for his entire life was thought."

In later years Kierkegaard was accustomed to spend days and weeks in practicing on himself different emotional and temperamental states, an exercise which he describes as "a kind of nimble dancing in the service of thought. ' ' This making of himself an instrument for the exploration of the passions, by which he attained an extraordinary command of the scale of human feeling, was undoubtedly to a large extent made possible by the strange training of the imagination above described, fantastic as it must seem to all straightforward souls.

A final and decisive paternal influence was that which had its source in the elder Kierkegaard's sombre religiosity. The sternness of the parental discipline, indeed, gave the boy a lofty impression of duty, for he was trained to a strict obedience. Not that he was enmeshed in the web of a multiplicity of petty obligations, but with respect to the few commands that were laid upon him, it was the parental principle that no evasion was to be tolerated. Kierkegaard's large esthetic sensibility thus received a restraining and balancing counterpoise in the form of a strong sense of the value of obedience, of authority, and even of an uncompromising severity. This left a permanent mark upon his thought.

But it was in connection with the teaching of the Christian dogma that the father's influence was most pregnant with significance. The boy heard little at home about the gentle Christmas Child, but so much the more of the suffering and crucified Saviour. These impressions were brought so vividly to bear upon the boy's inner life as to do violence to his personality as a child; and in conjunction with his native melancholy they helped to rob his childhood of its natural heritage of spontaneity and immediacy. "I have never," he says, "enjoyed the happiness of being a child." This "well-meant violence" on the part of his father he later came to regard as a training, unnatural to childhood and youth, but which nevertheless later, when he was mature enough to profit by it, became his most precious spiritual inheritance. But his childhood, he avows, was burdened with impressions "too heavy to bear, even for the old man who laid them upon me." "My father's error, however, was not to be lacking in love, but to forget the difference between a child and an old man." The misunderstanding, indeed, served to strengthen the bonds of filial piety. "To love one who makes me happy, is, viewed in reflection, an imperfect form of love. To love one who from motives of malevolence makes me unhappy, is virtue. But to love one who makes me unhappy because he loves me, and hence by a misunderstanding, but nevertheless really makes me unhappy, that is a form of love which to my knowledge has never yet been described, a form of love, nevertheless, which when viewed in reflection, is revealed as the normal form of love." The religious discourses of Kierkegaard's authorship were repeatedly dedicated in their successive issues to "my deceased father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard, formerly a merchant of this city".

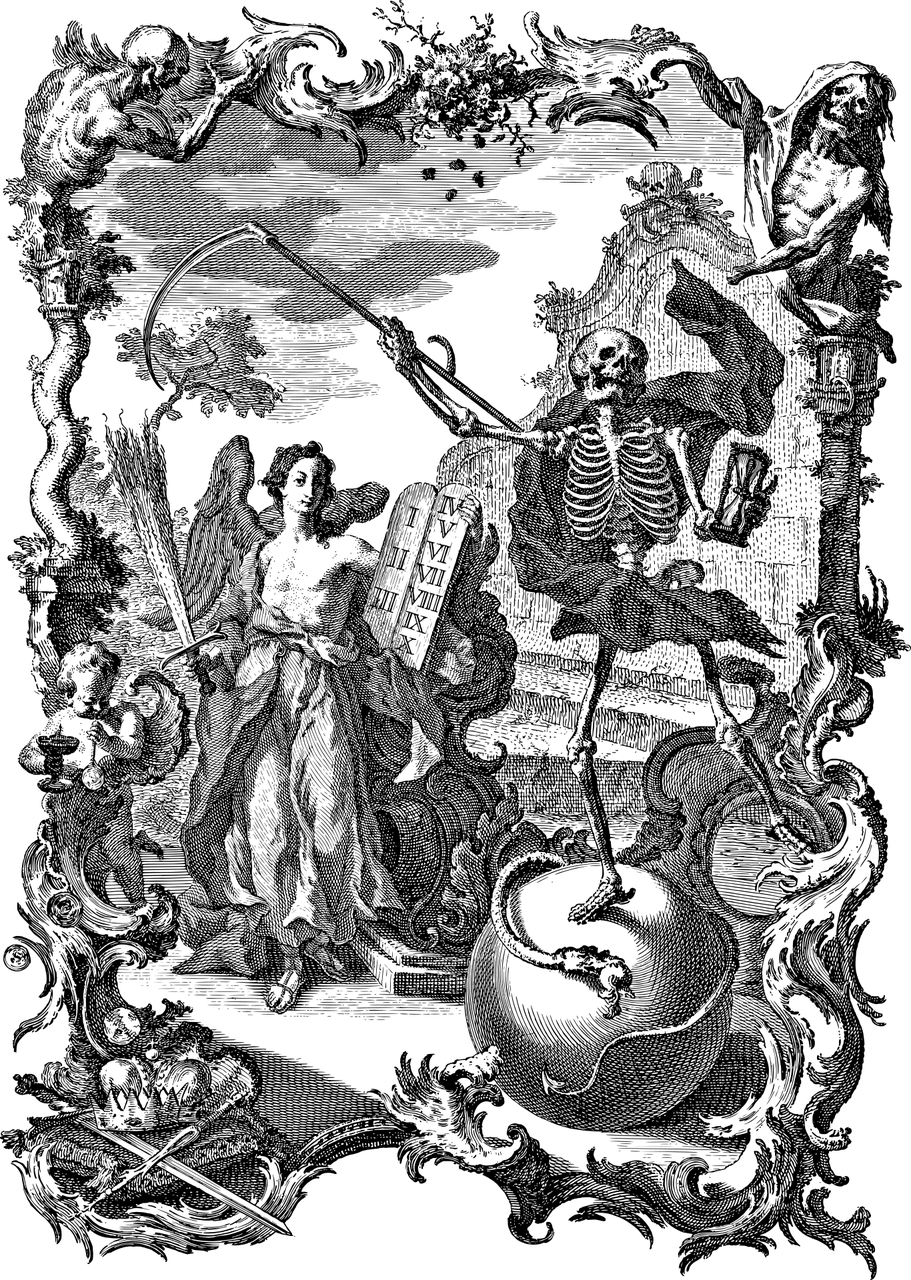

Fot. Pixabay

SÖREN KIERKEGAARD by David F. Swenson, Scandinavian Studies and Notes, Vol. 6, 1.02.1920